Many books have been written about George Washington the general, the president and even the politician. Far fewer have been written about the young Washington and what characteristics of his led him to become the leader of men that we have come to know; was it nature, nurture or some combination of these influences.

Washington was born the third son of a second-level planter in the Northern Neck region of the Colony of Virginia with dim prospects for ever becoming a member of the landed gentry, as then the eldest son in a family would be the principal heir of an estate. Washington’s father died when he was eleven leaving him the 600-acre Ferry Farm on the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg, VA. His older brother, Lawrence, inherited the plantation on the Potomac River known as Little Hunting Creek, later named Mount Vernon by Lawrence.

After his father died, Washington lived with his mother at Ferry Farm where he learned discipline and character with Lawrence serving as a surrogate father and Mount Vernon becoming a second home. Washington learned gentlemanly behavior from his English-schooled brother and his association with the Fairfax family headed by Thomas 6th Lord Fairfax, owner of the Northern Neck Proprietary, who took a liking to young George. These associations would be important for George as he matured and later became involved in the politics of Fairfax County, the Virginia Colony and later that of the new country.

Washington was largely a self-taught man who began his self-education by using his father’s equipment to learn surveying. By 1749 at the age of 17 he received a surveyor’s certificate from The College of William and Mary and was appointed chief surveyor for Culpeper County thereby establishing him as a respected tradesman.

In 1752, Washington, now 20-years-old, was appointed a Major in the Virginia militia beginning his military career. George’s military experience grew over the next two years on two separate expeditions to remove the French from the Ohio Country. The failures of both of these missions resulted in 1755 in the formation of the Virginia Regiment with Washington in command with the daunting mission to defend Virginia’s western frontier. The choice of Washington to command the regiment was based on his knowledge of the frontier and his previous military experience. As commander of the regiment, 1756-1758, Washington had mixed success, but the experience gained during this period would prove invaluable later in his career. 3 4

Frustrations & Struggles

Remember that Washington was only 24-years-old when he received approval from the House of Burgesses to begin construction of Fort Loudoun, manage the Virginia militia, and serve as the British’s eyes and ears on the western frontier. After his defeat at Fort Necessity, Washington practiced extreme discipline and had high expectations for the militia. Dr. Carl Ekberg explains, Washington kept this book [A Treatise of Military Discipline by Humphrey Bland] by his bedside and recommended it to all of his junior officers. Immersing himself in it, Washington both learned about military affairs and improved his prose style, which became clearer and more grammatical over time. Burning with high ambitions, but understanding his limitations from lack of formal schooling, Washington was a relentless self-improver, an autodidact par excellence. 5

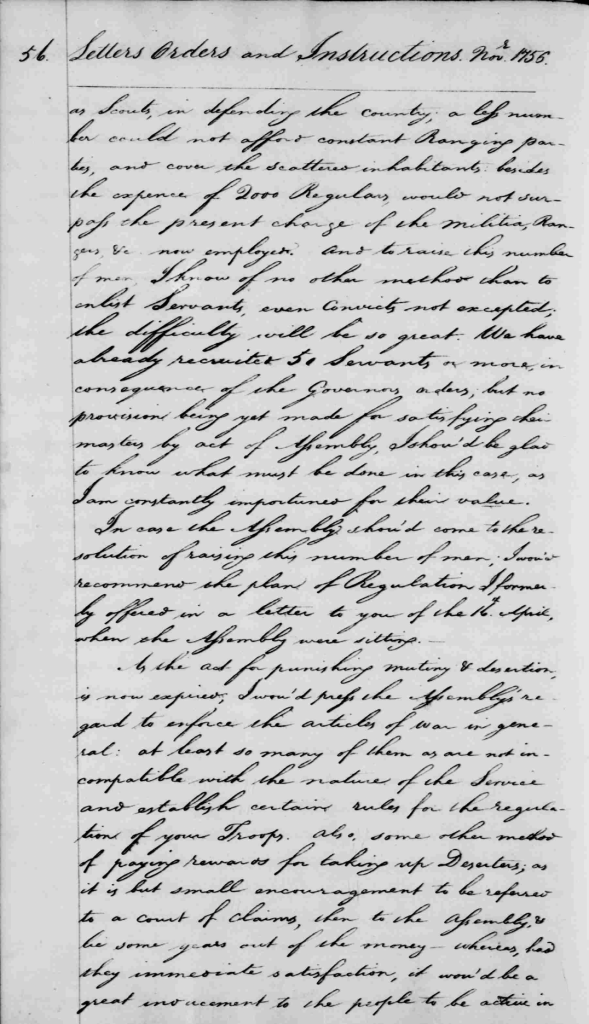

You can see Washington’s discipline in the orders he wrote for the militia:

I am loath to leave this [place]. I declare, upon my honor, I am not, but had rather be at Fort Cumberland, (if I could do the duty there), a thousand times over: for I am tired of the place, the inhabitants, and the life I lead here.

From George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie, 2 December 1756 6

- Orders for the Militia, Winchester, 15 May 1756: The commanding Officers of the Militia left at this place, are to order all their Men to be under arms at Retreat-beating this Evening: and are to acquaint them, that if any of them desert, they will be immediately draughted as Soldiers into the Virginia Regiment. 7

- Orders, Winchester, Wednesday, May 19th 1756: Ensign McCarty is ordered to make all the Soldiers now left in town, encamp; and to see that the Rolls are called over every night at Tattoo – and to order that they all remain in their Tents after that time; and do not presume afterwards to come into Town, to breed Riots and Quarrels, which they are but too subject to, when they get drunk. 8

- Orders, Winchester, Friday, May 21st 1756: Colonel Washington now expressly orders, that every Soldier who does not appear on the parade at the usual hours, with his Firelock bright and clean, and otherwise in good order, according to the custom of the Army; that he shall be immediately confined and tried by a Court Martial. 9

- Orders, 21–22 May 1756: An Order was lately given out for the Officers to see that the men kept their arms constantly in good repair: But as the sense of this order seems to have been mistaken, by its not being strictly complied with – (the Guns perhaps may fire;) but that is not all that is expected. Therefore Colonel Washington now expressly orders, that every Soldier who does not appear on the parade at the usual hours, with his Firelock bright and clean, and otherwise in good order, according to the custom of the Army; that he shall be immediately confined and tried by a Court Martial. 10

Tippling Houses

And then there were the tippling houses, which the men frequented, much to Washington’s chagrin. He wanted to reign in the chaos and debauchery amongst the men and instead have order and formality in the militia. Washington even went so far as to ask, if not outright beg, Stephen Rollins, owner of one of the tippling houses, to stop serving alcohol to the soldiers, to no avail:

To Charles Lewis, Winchester, 4 June 1756: All the Soldiers that are unemployed, in the aforesaid Duty, are to be formed into Squads and duly exercised and regularly trained twice or thrive a-day – You must endeavour to inculcate due obedience upon the new Recruits – and to discourage Swearing and Drinking. All that are brought to this place you are to receive, and put under proper command and regulation until I arrive, and to take care that none of them desert; if they do, to send immediately after them.

From Robert Stewart, Maidstone, June 20th 1756: One [Stephen] Rollins who keeps a little tippling House here is in some measure the cause of that infamous and pernicious practice when I first arrived here I sent a Serjeant to him desiring him at his Perril not to sell Liquor to the Soldiers, this he paid no regard to, I then went to him and told him the terrible consequences of hurting the Service by making the Soldiers Drunk especially at such a Juncture but he still parsever’d. I then plac’d a Centary at each of his Doors with orders not to suffer a man of the Detachment to go in the House, but most of the Centrys were corrupted by his giving liquor for liberty to supply others.

From George Washington to John Robinson, 9 November 1756: As Fort Loudon must be supported – I would represent the prejudice we suffer by the number of Tippling-houses kept in this town; by which our men are debauched, and rendered unfit for duty, while their pay lasts… 13

Did you know?

In August 1755, the General Assembly of Virginia passed an act that called “for better regulating and training the Militia” in which soldiers in the militia weren’t allowed to sell any of their weapons or clothing to civilians.

In an Evening Order from Winchester on May 26, 1756, it says, If the people of the Town or Country, have any arms, clothes, Blankets, &c. &c. Belonging to the Soldiers, which they have bought; they are desired to give them in immediately to the commanding officer: If they are found in their possession after issuing this order; they must expect to be prosecuted to the utmost rigour of the Law; which has laid penalty of twenty pounds (upon any person who buys or exchanges any arms, Clothes &c. with a Soldier;) to be paid to the Informer. 14

You can find the original act on Encyclopedia Virginia.

Desertion

I recd Your Journal relating to the Militia which gives me some surprize to observe their dastardly Behavior, in deserting & returning Home, I am sorry their Officers had no better Command over them, & indeed I always was of Opinion they wd not answer my Intentions in sending them to Winchester.

From Robert Dinwiddie, Williamsburg May 27th 175615

Another big struggle for the disciplined Washington was desertion – not everyone shared his dedication and loyalty to the British. You can sense his frustration and desperation to get his men to straighten up and fight for the Crown. He employed a few tactics to discourage desertion: public executions, regular roll calls, and mercy via enlistment into the Virginia Regiment.

Public Executions

The Spirrit of Desertion was of late so prevalent here, that I once dreaded no other expedient than Hanging or shooting could affectually crush it.

From Robert Stewart, Maidstone, June 20th 1756 16

In an order he issued on 18 May 1756, Washington wants to warn the new recruits of the consequences for deserting by executing a Sergeant who had been sentenced to death for his desertion:

All the troops are then to appear on the parade – Captain Woodward is to read the articles of war to them, and acquaint them, that his Honour, Governor Dinwiddie has been pleased to approve of the Sentence of the General Court Martial, which condemned Sergeant Lewis, and has sent up his death-warrant – and that he will, in consequence thereof, be shot as soon as the new Recruits arrive from Fredericksburgh. It is hoped all of his way of thinking will take warning from his death – The caution is unnecessary to the Brave, who are stimulated by those noble principles of Honor and Courage.

Washington often used this visual, graphic tactic to warn new recruits of his zero tolerance policy for desertion. In a letter he wrote to Governor Dinwiddie, Washington says,

The spirit of Desertion was so remarkable in the Militia […]

[Henry Campbell was] “a most atrocious villain” [who Washington thought was] “worthy an Example against Desertion… whose execution I have delayed until the arrival of the Draights. These Examples, and proper encouragement for good Behaviour, will I hope, bring the Soldiers under proper Discipline.

To Dinwiddie, Winchester, 23 May 1756 17

Strict orders in camp

In an effort to curtail desertion, Washington even implemented regular, frequent roll calls throughout the day:

The Rolls must be called regularly three times a-day; and every precaution taken to prevent desertion: If it so happens that any do desert; you are to send Officers immediately after them. You are not to provide the men with necessaries there (unless it should be the Governours orders) They must wait until they come to this place. When a Senior Officer arrives, give him these Instructions, and put yourself under his command.

From George Washington to Henry Woodward, 24 May 1756 18

Mercy via Enlistment in the Virginia Regiment

Fort Loudoun garrisoned men from the Virginia Militia as well as the Virginia Regiment, and it’s important to understand the difference between the two. The Virginia Militia was made up of free, able-bodied men who could fight but who weren’t formally trained soldiers. The Virginia Regiment, on the other hand, comprised soldiers trained by and for the British Crown. The Virginia Militia was a little harder to control and keep in order, so Washington started a policy of immediately drafting any militiaman who deserted into the Virginia Regiment:

- Orders to the Militia, Winchester, 15 May 1756: The commanding Officers of the Militia left at this place, are to order all their Men to be under arms at Retreat-beating this Evening: and are to acquaint them, that if any of them deser, they will be immediately draughted as Soldiers into the Virginia Regiment. 19

- Memorandum respecting the Militia, Winchester, 18 May 1756: [L]ast Night Mr Bullet the Officer who I had sent out to returnd with 14 of the deserters who to avoid punish inlisd in the V.R. [Virginia Regiment] 20

Winter 1757-58: Illness

In addition to the tippling houses, desertion, and all-around disobedience from the militia, Washington also faced sickness. He was sick with dysentery during the winter of 1757-1758 and returned to Mount Vernon for 4 months to recuperate.

While Washington was fighting his own illness, the men at Fort Loudoun were sick, too:

- To George Washington from Charles Smith, 26 July 1758: The Small Pox has not Spread in Town as yet, but the Flux is Very bad in the fort, there has been two of the old Regiament Dead, and five of the New, Since Your departure. I am but weack in the Garrison. 21

- Charles Smith wrote Washington on February 23, 1758: Our Stone Masons has been Sick Ever Since you have been away, and our Stone Work is much Behind hand. 22

Note: The “flux” is dysentery.

Washington’s Resignation in 1758

When officers of the Virginia Regiment at Fort Loudoun learned of Washington’s resignation in late 1758, they wrote an emotional address to him; we’ve pulled some of the highlights from their letter:

The ⟨happine⟩ss we have enjoy’d and the Honor we have acquir’d, together with the m⟨utua⟩l Regard that has always subsisted between you and your Off⟨icers,⟩ have implanted so sensible an Affection in the Minds of us all, that we cannot be silent at this critical Occasion.

In our earliest Infancy you took us under your Tuition, train’d us up in the Practice of that Discipline which alone can constitute good Troops, from ⟨the⟩ punctual Observance of which you never suffer’d the least Deviation.

Your steady adherance to impartial Justice, your quick Discernment and invarable Regard to Merit, wisely intended to inculcate those genuine Sentiments, of true Honor and Passion for Glory, from which the great military Atcheivements have been deriv’d, first heighten’d our natural Emulation, and our Desire to excel. How much we improv’d by those Regulations […] we submit to yourself, and flatter ourselves, that we have in a great Measure answer’d your Expectations.

Judge then, how sensibly we must be Affected with the loss of such an excellent Commander, such a sincere Friend, and so affable a Companion. How rare is it to find those amiable Qualifications blended together in one Man?

Who in short so able to support the military Character of Virginia?

Your approv’d Love to your King and Country, and your uncommon Perseverance in promoting the Honor and true Interest of the Service, convince us, that the most cogent Reasons only could induce you to quit it.

Frankness, Sincerity, and a certain Openness of Soul, are the true Characteristics of an Officer, and we flatter ourselves that you do not think us capable of saying anything, contrary to the purest Dictates of our Minds.

Address from the Officers of the Virginia Regiment, 31 December 1758 23

You may read the letter in its entirety here.

Washington’s response to his officers of the Virginia Regiment was equally emotional and complimentary; again, we’ve pulled a few highlights from this letter:

If I had words that could express the deep sense I entertain of your most obliging & affectionate address to me, I should endeavour to shew you that gratitude is not the smallest engredient of a character you have been pleased to celebrate; rather, give me leave to add, as the effect of your partiality & politeness, than of my deserving.

That I have for some years (under uncommon difficulties, which few were thoroughly acquainted with) been able to conduct myself so much to your satisfaction, affords ⟨me⟩ the greatest pleasure I am capable of feeling; as I almost despared of attaining that end—so hard a matter is it to please, when one is acting under disagreeable restraints! But your having, nevertheless, so fully, so affectionately & so publicly declared your approbation of my conduct, during my command of the Virginia Troops, I must esteem an honor that will constitute the greatest happiness of my life, and afford in my latest hours the most pleasing reflections. I had nothing to boast, but a steady honesty—this I made the invariable rule of my actions; and I find my reward in it.

From George Washington to the Officers of the Virginia Regiment, 10 January 1759 25

You may read the letter in its entirety here.

Washington officially resigned his command of Virginia forces on 23 January 1759, which then went to Colonel William Byrd III.

Election of George Washington to Virginia House of Burgesses 1758

The House of Burgesses was created in 1642 as an instrument of government with the royal governor and the Council of State. After Virginia declared independence, the House became the House of Delegates as the lower house of the General Assembly. Elections at that time were conducted by voice vote of landowners. The county sheriff, a clerk and a representative of each candidate would sit at a table. The elector approached the table and openly voiced his vote. Each voter had two votes.

George Washington ran for election to the House of Burgesses from Frederick County in 1755 and lost to Hugh West and Thomas Swearingen. In 1758, Washington ran again. As he was involved in the French & Indian War, Colonel James Wood, Sr. managed his campaign and represented him at the election. Wood obtained 160 gallons of alcoholic drinks, distributing them free to 391 voters in Frederick County, which was a common practice at the time.26

Running with Washington were Thomas Bryan Martin, Hugh West and Thomas Swearingen, the latter two (West and Swearingen) incumbents in the House of Burgesses. Washington and Martin were elected, with Washington successfully gaining reelection in 1761. In 1765, he ran and won a seat to represent Fairfax County, which he held until 1775 when the American Revolutionary War broke out.

| Did you know? Washington spent £39.6 on free food and alcohol to hand out during the Election of 1758, which is more than $2,500 in today’s currency! 27 28 |

- Peale, C. W. (2019, February 15). Portrait of George Washington. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page ↩︎

- McRae, J. C. & White, G. G. (ca. 1867) “Father, I cannot tell a lie: I cut the tree” / painted by G.G. White ; engraved by John C. McRae. , ca. 1867. New York: Published by John C. McRae, 100 Liberty St. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2006678326/. ↩︎

- Lewis, T. A. (2006). For king and country : the maturing of George Washington, 1748-1760. Castle Books. ↩︎

- Stewart, David O. GEORGE WASHINGTON : The Political Rise of America’s Founding Father. S.L., Dutton, 2022. ↩︎

- Ekberg, C., Freeman, E., Ross, L., Evans, D., Emmart, S., French and Indian War Foundation, Smith, S., Smith, D., Swaim, S., Rios, D., Cherry, E., Zuckerman, C., Bartlett, M., O’Connor, A., Kalbian, M., & Grosso, D. (n.d.). Celebrating Winchester’s 275th Birthday: A historical perspective. In George Washington Hotel & C-SPAN, Celebrating Winchester’s 275th Birthday (pp. 1–2). https://fiwf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/FIWF-Newsletter_V15No5-SpecialEdition_2020.pdf ↩︎

- “From George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie, 2 December 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-04-02-0012. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 4, 9 November 1756 – 24 October 1757, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 34–37.] ↩︎

- “Orders for the Militia, 15 May 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-03-02-0132. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 3, 16 April 1756–9 November 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 136–137.] ↩︎

- “Orders, 19 May 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-03-02-0160. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 3, 16 April 1756–9 November 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, p. 164.] ↩︎

- “Orders, 21–22 May 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-03-02-0167. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 3, 16 April 1756–9 November 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, p. 169.] ↩︎

- “Orders, 21–22 May 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-03-02-0167. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 3, 16 April 1756–9 November 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, p. 169.] ↩︎

- Long Room Archive — Fraunces Tavern® Museum. (n.d.). Fraunces Tavern® Museum. https://www.frauncestavernmuseum.org/long-room-archive ↩︎

- Washington, G. (1756) George Washington Papers, Series 2, Letterbooks 1754 to 1799: Letterbook 4, Sept. 19, 1756. – April 26, 1758. [Manuscript/Mixed Material] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mgw2.004/. ↩︎

- Citation: “From George Washington to John Robinson, 9 November 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-04-02-0002. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 4, 9 November 1756 – 24 October 1757, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 11–18.] ↩︎

- “Evening Orders, 26 May 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-03-02-0178. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 3, 16 April 1756–9 November 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 177–178.] ↩︎

- “To George Washington from Robert Dinwiddie, 27 May 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-03-02-0180. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 3, 16 April 1756–9 November 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 178–182.] ↩︎

- “To George Washington from Robert Stewart, 20 June 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-03-02-0208-0001. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 3, 16 April 1756–9 November 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 207–210.] ↩︎

- “From George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie, 23 May 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-03-02-0169. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 3, 16 April 1756–9 November 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 171–174.] ↩︎

- “From George Washington to Henry Woodward, 24 May 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-03-02-0174. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 3, 16 April 1756–9 November 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, p. 175.] ↩︎

- “Orders for the Militia, 15 May 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-03-02-0132. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 3, 16 April 1756–9 November 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, pp. 136–137.] ↩︎

- “Memorandum respecting the Militia, 18 May 1756,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-03-02-0152. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 3, 16 April 1756–9 November 1756, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1984, p. 151.] ↩︎

- “To George Washington from Charles Smith, 26 July 1758,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-05-02-0273-0001. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 5, 5 October 1757–3 September 1758, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988, pp. 331–332.] ↩︎

- “To George Washington from Charles Smith, 23 February 1758,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-05-02-0069. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 5, 5 October 1757–3 September 1758, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988, pp. 96–97.] ↩︎

- “Address from the Officers of the Virginia Regiment, 31 December 1758,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-06-02-0147. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 6, 4 September 1758 – 26 December 1760, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988, pp. 178–181.] ↩︎

- Encyclopedia Virginia. (2021, February 11). William Byrd III – Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/903hpr-aedd9d43d74f08d/ ↩︎

- “From George Washington to the Officers of the Virginia Regiment, 10 January 1759,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-06-02-0152. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 6, 4 September 1758 – 26 December 1760, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988, pp. 186–187.] ↩︎

- Grosso, D. (2021). Notes from the President. https://fiwf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/FIWF-Newsletter_V16No3-6p_Summer-2021.pdf ↩︎

- “To George Washington from Charles Smith, 26 July 1758,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-05-02-0273-0001. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 5, 5 October 1757–3 September 1758, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1988, pp. 331–332.] ↩︎

- Inflation Rate between 1755-2024 | Inflation Calculator. (n.d.). https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1755?amount=50.23 ↩︎

This exhibit was made possible, in part, by a grant from the VA250 Commission in partnership with Virginia Humanities.

Exhibit researched and written by Jess Pritchard-Ritter, Donna Leight, and David Grosso. Created by For the Love of History Consulting, LLC.