The French & Indian War

Jumonville Glen

| Want to learn more about Jumonville Glen? The National Park Service (NPS) has an audio clip from their self-guided tour. The American Battlefield Trust has an essay on the skirmish. The Smithsonian Magazine wrote an article called, When Young George Washington Started a War. Dr. Carl Ekberg wrote a piece called, Washington, Gist, & Half-King Start a World War in the French & Indian War Foundation’s Volume 15, Issue 4 Newsletter from Fall 2020. Mount Vernon has an essay on the Jumonville Glen Skirmish. |

But why did it start?

Fort Necessity in a Nutshell

“The debacle at Fort Necessity in July 1754 is one of most compulsively studied episodes in George Washington’s life, for it was his elementary school in frontier warfare; defeat is a harsher but better schoolmaster than victory.”

Dr. Carl Ekberg

For more on Washington’s humiliation by Louis Coulon de Villiers at Fort Necessity, see Dr. Ekberg’s essay, George Washington’s Luckiest Day.

| Further Reading National Park Service’s Battle of Fort Necessity (essay) National Park Service’s Fort Necessity National Battlefield (video) A Charming Field for an Encounter (e-book) |

Braddock’s Defeat at the Battle of the Monongahela

We need to talk about one more French & Indian War story before we head to Fort Loudoun in Winchester, Virginia.

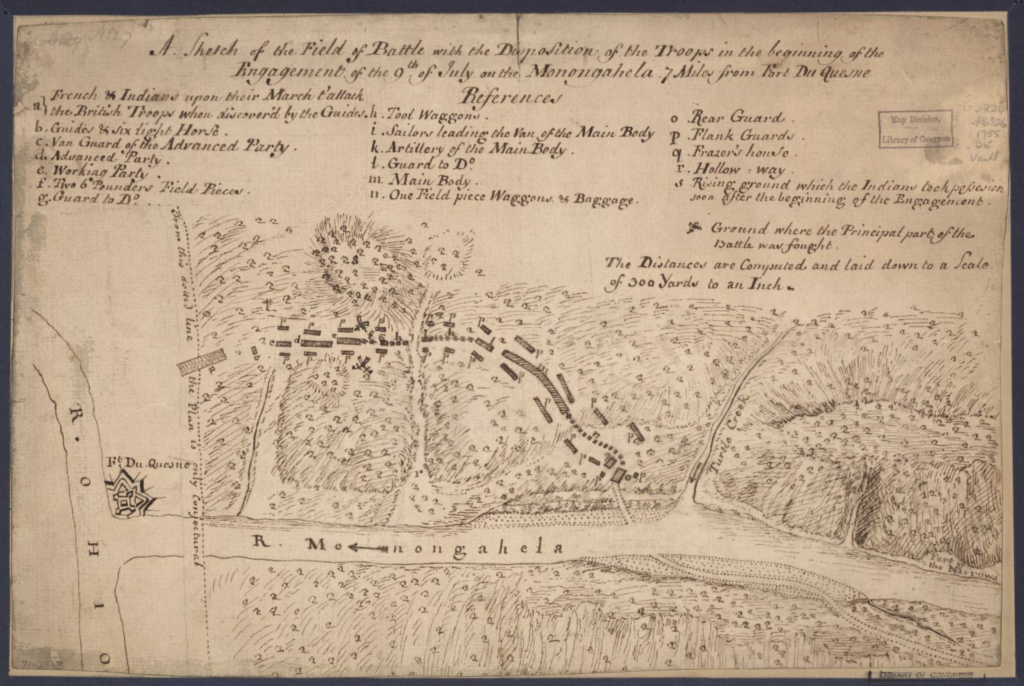

Following Washington’s defeat at Fort Necessity, the British sent an army of 5,000 men to Virginia under the command of General Edward Braddock in 1755 to capture Fort Duquesne and remove the French from the Ohio Country. Unfortunately, this expedition ended in disaster with two-thirds of the command lost to the French and their Indian allies at the Battle of the Monongahela on July 9, 1755.13

Washington, serving as aide-de-camp to Braddock on the expedition and one of the few surviving officers, led the retreat. Braddock himself was mortally wounded in the battle.

The defeat of Braddock’s army left the western frontier unprotected and prompted the Virginia Colony to form the Virginia Regiment to be comprised of 10 companies of 100 men each with the responsibility of defending the frontier from the Potomac R. to the North Carolina border 8 . George Washington was appointed Colonel in command of the regiment, a position he held from 1756 through 1758 when the war on the western frontier ended.

The events in North America led to a formal declaration of war by the British in 1756 resulting in the onset of the Seven Years War and the French and Indian War in North America. As it turns out Washington’s actions at Jumonville Glen changed the course of world history and resulted in Britain becoming the predominant naval power in the world and a pre-eminent colonial world power.

| Further Reading Ben Franklin’s World Podcast | Episode 060: David Preston, Braddock’s Defeat: The Battle of the Monongahela (podcast) French & Indian War Foundation Newsletter | Volume 7, Issue 1, February 2012 | Braddock’s Road, The Final Thrust: Fort Cumberland to the Monongahela, written by Norman Baker (book excerpt) Mount Vernon’s Interview with David Preston (transcribed interview) Braddock’s Road: Mapping the British Expedition from Alexandria to the Monongahela by Norman Baker (book) |

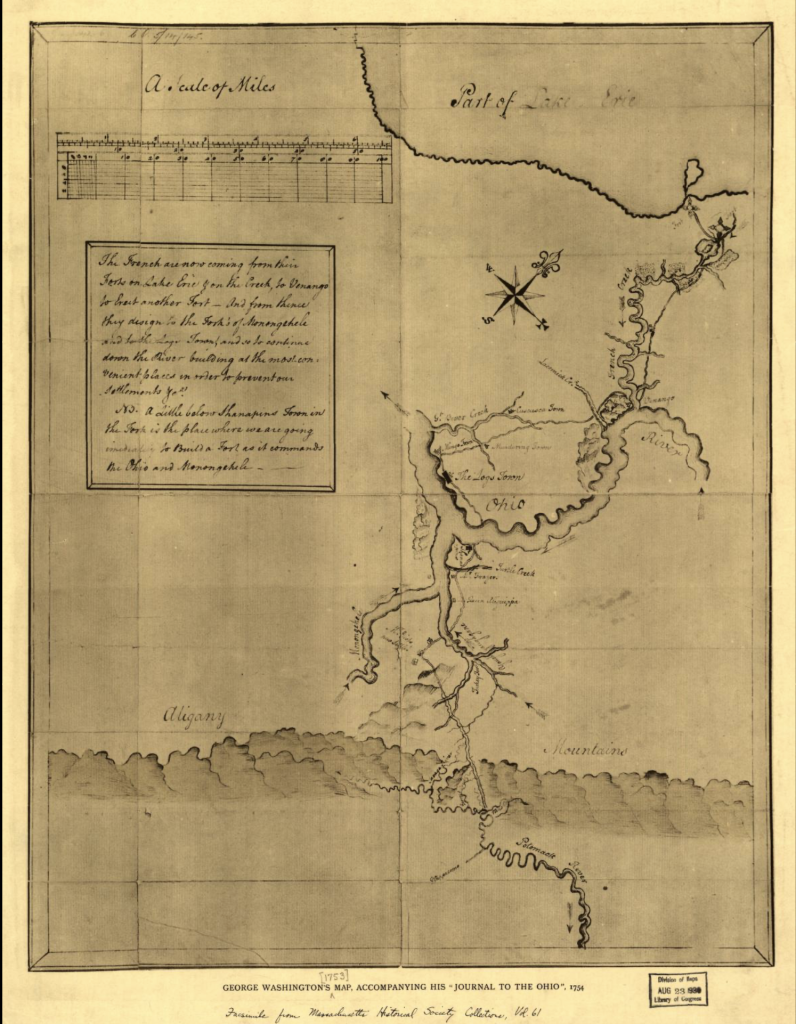

- Washington, G. (1754) George Washington’s map, accompanying his “journal to the Ohio”. [Boston] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/99446116/. ↩︎

- “Commission from Robert Dinwiddie, 30 October 1753,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-01-02-0028. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, vol. 1, 7 July 1748 – 14 August 1755, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1983, pp. 56–60.] ↩︎

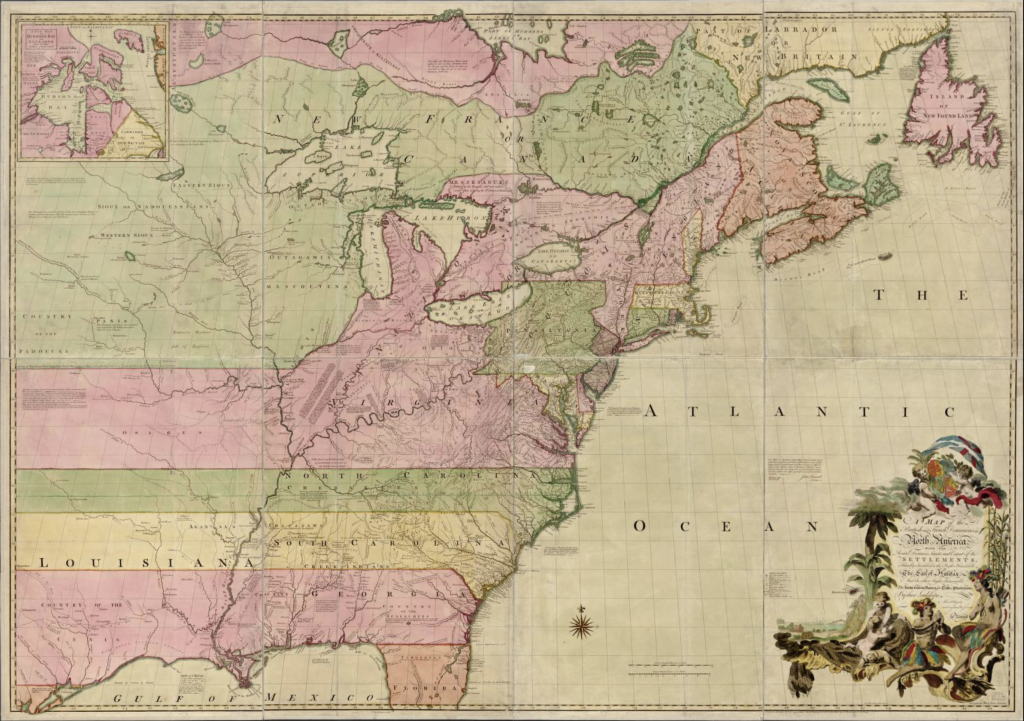

- Mitchell, J., Kitchin, T. & Millar, A. (1755) A map of the British and French dominions in North America, with the roads, distances, limits, and extent of the settlements, humbly inscribed to the Right Honourable the Earl of Halifax, and the other Right Honourable the Lords Commissioners for Trade & Plantations. [London; Sold by And: Millar] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/74693173/. ↩︎

- Cross, D. (2020b, August 24). A Snapshot of George Washington EP. 9: More than a Messenger. YouTube. https://youtu.be/dn-BE31RBk4?si=d1AkNsNzRuE3lP1m ↩︎

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. (1859). Death of Jumonville Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/58f3ab90-2e68-0133-bc04-58d385a7b928 ↩︎

- Anderson, F. (2001). Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. Random House. ↩︎

- Anderson, F. (2001). Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. Random House. ↩︎

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. (1751 – 1885).Robert Dinwiddie, governor of Virginia. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-2440-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 ↩︎

- Anderson, F. (2001). Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. Random House. ↩︎

- Anderson, F. (2001). Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. Random House. ↩︎

- Anderson, F. (2001). Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. Random House. ↩︎

- The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. (1879). Death of General Braddock Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-f49d-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99 ↩︎

- Anderson, F. (2001). Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766. Random House. ↩︎

- (1755) A sketch of the field of battle with the disposition of the troops in the beginning of the engagement of the 9th of July on the Monongahela 7 miles from Fort Du Quesne. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/gm71002313/. ↩︎

This exhibit was made possible, in part, by a grant from the VA250 Commission in partnership with Virginia Humanities.

Exhibit researched and written by Jess Pritchard-Ritter, Donna Leight, and David Grosso. Created by For the Love of History Consulting, LLC.