Researched and written by Donna Leight, 2025

From Wilson to Denny to Maloy

Two years into America’s Civil War, Reverend Norval Wilson and his wife Cornelia sold their Fort Hill home to William R. Denny, on September 7, 1863, for $6000 in Confederate and Virginia Treasury notes. Denny immediately sold the property to Hugh and Anna Maloy the next day for $8250 in Confederate money. Both deeds allowed Rev. Wilson and his wife to remain in the home until October.1 By this time, Winchester was heavily impacted by America’s Civil War, as summarized in the previous story. The first battles of Kernstown and Winchester happened early that year and in just a few weeks, the battle at Antietam would fill Winchester’s streets, churches, and fields with the injured, dying, and dead.

Who Was William Ritenour Denny (1823-1904)?

While William R. Denny never lived in the home, he was a prominent citizen of Winchester, and a brief biography is included in this story. He married Margaret Ann Collins, the daughter of a Methodist minister, and they had seven or eight children.

As mentioned in a previous story, he was instrumental in the formation of the new congregation of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South in 1858, organizing the construction of a new church on Braddock Street on a lot he had purchased.2 3 His son Collins Denny was a Bishop in that church.4

The 1860 U.S. Census shows Denny as a merchant, married with four young children and a twenty-two-year-old mulatto male domestic servant. The 1860 Slave Schedule shows also owned an enslaved fourteen-year-old mulatto boy.5

A year later, at the outbreak of the Civil War, Denny enlisted with the Confederacy and was made Lieutenant Colonel of 31st Militia Regiment, attached to Stonewall Jackson’s brigade. During the first battle of Manassas, he was commandant of the forces at Winchester and was later taken prisoner by Federal soldiers.6

According to an 1867 Freedmen and Refugee Register, following the war, Denny provided rations to a destitute elderly black woman named Ellen, age 71.7

In June 1868, Denny was present when the remains of Gen. Daniel Morgan were moved to Mt Hebron Cemetery, where Denny was a member of the Board of Managers.

The following summation of William R. Denny’s impressive accomplishments appeared upon his death:

“…he was a member of Mark Twain’s “Innocents Abroad” party and was an intimate friend of Mr. Clemens, traveling with him extensively. He was the president of the Winchester and Potomac railroad. He started the Winchester paper mills, the Winchester Gas Co. and the Union bank. Colonel Denny built the Southern Methodist church. He started the movement to remove 829 unknown Confederate dead to the Stonewall Cemetery in Winchester, and was the leading spirit that carried into execution, the erection of the monument to the memory of the Confederate dead, dedicated in 1875. He was also one of the founders of Mount Hebron cemetery. Colonel Denny was worshipful master of Hiram Lodge of Masons and assisted in initiating President McKinley when he was a soldier during the Civil War.”

“Death of Col. Denny: An Old Soldier and Useful Man Passes Away” 8

Note that “Innocents Abroad; The New Pilgrim’s Progress” was a popular and humorous travel book written by “Mark Twain” (Clemens) about his voyage on the Civil War era steamship U.S.S. Quaker City, carrying American travelers on a five-month tour to France, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Egypt, and the Holy Land in the summer of 1867. Denny was the only Virginian on board.

William R. Denny, Margaret, and at least three of their children are buried in Mount Hebron Cemetery in Winchester Virginia.9

Who Was Hugh C. Maloy?

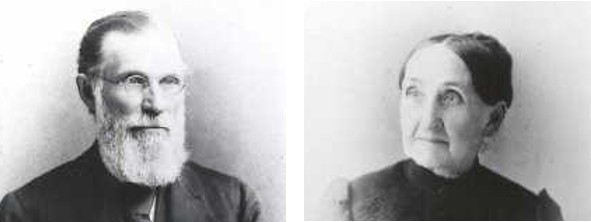

Hugh Maloy (1817-1864) was an Irishman born in Pennsylvania. His wife, Anna Dinkle (1820-1904) was from York, Pennsylvania. Hugh came from a family of tradesmen. The 1860 Census from Philadelphia shows that his father Daniel was an Irish immigrant who worked as a carpenter. His uncle Peter was a cigar maker. The 1870 Pennsylvania census shows that Hugh’s brother Daniel was a paper mill superintendent, brother Thomas was a coal miner, and his sister Josephine married a painter.10

The 1860 Virginia census shows Hugh as a farmer in Frederick County Virginia.11 We don’t know where he farmed, and it’s not known why he moved to Winchester. Unlike the Fort Hill property owners before him, he was not a lawyer, a politician, or a preacher. When he bought the property in 1863, he would not have been able to continue any significant farming at 419 N. Loudoun, as the property only had a small garden area.

The manner in which the house was purchased is worth noting. As mentioned above, William R. Denny purchased the home from Rev. Wilson on September 7, 1863 and then sold it the next day to the Maloy’s.12 Denny had many properties in Winchester, and it would have been easy for him to make the purchase. Perhaps Rev. Wilson sought Denny’s help in securing the home for the Maloy’s. It is known that Anna Maloy attended the Market Street Methodist Church where Rev. Wilson had preached.13 Denny and Maloy may have been friends, and this may have been a friend helping a friend. There may have been some other arrangement in the background, not covered by the deed. Hugh Maloy may have been unwell and unable to farm. He died less than a year later. We may never know that part of the story.

By the time the Maloy’s bought the home, Winchester and the surrounding area had been dramatically impacted by the Civil War. Gettysburg had happened just two months earlier and some of its wounded and dead remained in area hospitals and graveyards. The effects of battles in Kernstown, Stephens Depot, Winchester and bloody Antietam lingered. Many struggled with the death of Stonewall Jackson in May 1863. They watched the war destroy homes and families. They were surrounded by mourning. Few families were spared the loss of a loved one.

The Maloy’s had five children, four daughters and one son. They had lost their youngest daughter Laura Katherine, age 9, in 1862, a year before they bought the home on Fort Hill. The remaining three daughters were aged 13-18 when the war began. Their son Samuel “Ellis”, was only 11, too young to fight in the war, but the children were exposed to the stresses of war.14 15 They saw mothers and fathers and children crying. They saw houses and churches in ruins. Soldiers used their backyard well, a remnant from old Fort Loudoun.

We don’t know why Hugh did not fight in the war. But we do know that he died on July 16, 1864, at the age of 47 from Typhoid fever, leaving Anna and their four children alone at their home on Fort Hill.16

Anna sold their home on Loudoun Street in war-torn Winchester in November 1867 to Phillip Lewis Carter (PCL) Burwell. It appears that the Maloy’s may have lived in the home beyond the sale. Per the deed, she was to “see that the house should be insured in some Insurance Company in at least the sum of $2000.” 17

Census data shows us that their oldest daughter, Ameilia, married Winchester blacksmith Theophalus “Monroe” Snapp in 1868. The second oldest daughter, Rebecca, married William H. Byers in 1877, a farmer at “Rose Knoll” near Shepherdstown. Their son Ellis married “Bertie” and was a farmer in Frederick County Virginia.18

Anna Maloy died in 1904 at the home of her daughter Ameila, on Fort Hill at 414 North Loudoun Street, just across the street from 419 North Loudoun Street, the home that she and Hugh had purchased in 1863. Per The Evening Star obituary, “Notwithstanding her illness and her advanced age, Mrs. Maloy retained her mental faculties to a remarkable degree.” 19 She was age 85.

Hugh, Anna, son Ellis, daughters Amelia and Laura, and other family members are buried at Mount Hebron Cemetery in Winchester Virginia.

- Winchester Virginia Deed Book 11, pages 163 and 171 ↩︎

- Morton, Frederic. The Story of Winchester in Virginia: The Oldest Town in the Shenandoah Valley. Heritage

Books, 2007. ↩︎ - Winchester Virginia Deed Book 10, Page 298 ↩︎

- Russell, William Greenway. What I Know About Winchester: Recollections of William Greenway Russell, 1800-

↩︎ - U.S. Slave Schedule 1860 ↩︎

- Cumberland Alleganian Newspaper Archives December 8, 1904, Page 5 ↩︎

- Destitute Refugee and Freedmen Register for Frederick and Clark Counties, VA, February 1867 ↩︎

- Cumberland Alleganian Newspaper Archives December 8, 1904, Page 5 ↩︎

- FindaGrave.com ↩︎

- U.S. Census Records 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900 ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Winchester Virginia Deed Book 11, pages 163 and 171 ↩︎

- The Evening Star, Winchester Virginia, June 27, 1904, Page 1 ↩︎

- U.S. Census Records 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900 ↩︎

- FindaGrave.com ↩︎

- Register of Deaths, Corporation of Winchester ,Virginia 1864 ↩︎

- Winchester Virginia Deed Book 11, pages 163 and 171 ↩︎

- U.S. Census Records 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900 ↩︎

- The Evening Star, Winchester Virginia, June 27, 1904, Page 1 ↩︎